Myth #12 All hunger is trustworthy

Myth #13 If you’re a teacher, then you’re doomed to being fat

Myth #14 You have to eat. Eating is a necessary addiction. All eating is fine.

One of my brothers used to live with an alcoholic. It was a weird time, and resulted in the police being called a number of times when the situation got out of hand.

She was fun, bright, vivacious. One of those characters who was magnetic, drew people to her, like moths to a flame.

The people didn’t usually stick around all that long, though. This girl’s addiction was the cause of her losing jobs, losing friends.

One of her mates pulled a gun on our flatmate, who had become like a member of the family. He tried to intervene when an incident was getting out of hand. Our flatmate left shortly after. Understandably.

She would not contribute to the shared house food, and instead spent all her money on booze.

Eating was cheating.

I, naively, made them food one time when they were having a party at our place. It hardly got touched.

Her drinking got out of hand. She stopped paying rent. My brother had to kick her out. They fell out, and where once they were very close, now they’re no longer friends.

Addictions can ruin things like that. When you just can’t stop, something else has to give, in a natural cause and effect.

“I don’t drink coffee because it’s addictive. Also it’s yuck!” 16 year old me was so young and naive.

“But sure, you’re addicted to other things, Lauren. We’re all addicted to food.”

“Does that count? We have to eat, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to live. I don’t think that’s an addiction.”

“Yea, but you can’t live without it. That’s the definition of an addiction.”

“Is an addiction not a want becoming a need, rather than a need just existing? Like an optional extra becoming ABSOLUTELY NECESSARY.”

A discussion between my friend Victoria and myself when I was 16 in Thailand, as we were volunteering, making salt licks for elephants in one of the national parks.

Where is the line between a healthy relationship with food and an addiction?

This article by Scientific American outlines the problem that our brains are hardwired to seek out calorie rich foods, and the rewards pathways (dopamine receptors) light up like a Las Vegas casino when we get them.

“The sticky part about studying food addiction is that, unlike cocaine or alcohol, humans can’t exactly drop it—cold turkey or not. “You can’t really quit food,” Avena says. And humans are hardwired, thanks to eons of evolutionary selection, to seek high-calorie foods to keep us going through lean times. But with subsistence hunting, gathering and farming now little more than a niche lifestyle choice in wealthy nations, a brain set up to reward super-rich calorie snacks is more of a hazard than a help.

“In one sense, we’re all addicted to food,” Kenny says. He points out, however, that many of the food items widely available today, say cheeseburgers and milkshakes, are like superfoods in terms of their calorie quantities. “This energy-dense stuff is very new to us as a species. It’s probably corrupting brain circuitry,” he says.”

So the reward circuitry in our brain basically gets addicted to salty sugary food when we eat it on the regular. Hmmmm. This is so well known that there are now things call the ‘Dopamine Diet’. Some research suggests that we get not one but two hits of dopamine in a meal – one when we eat the food, and another when the food arrives in our stomachs.

But we still need some food. So what’s a girl to do?

Bake more?

Where is the line between needing food to service energy needs, and NEEDING food, in a this-cheesecake-is-so-good-I-can’t-stop kind of a way?

In 2012, when I was at Teacher’s College, I moved to Palmerston North. I found a great flat with awesome flatmates, featuring a couple of guys in the Air Force. It was a cool house, and I felt very lucky to be there. It was a convenient 10 min walk from campus and it had a pool and a spa – I was living the dream. We had a shared bank account for bills and we shared food. The other 4 people that lived in the house were very fit and active, and ate a normal person amount of food. (a.k.a less than me.)

I took to playing ‘Camp Mother’ and would buy the groceries most weeks, thinking I was being super helpful. It was good to have fruit and veg in the house, and I was used to a full-to-overflowing fridge and pantry.

It started out fine enough, but as the year progressed, I discovered that Teacher’s College might actually be a little bit challenging – 12 papers in a year was quite a bit, plus 16 weeks of actual teaching experience. We had a paper for something or other that was worth 50% of your grade due every other week.

The more the year progressed, the more I had to bribe myself to sit still and do my work, and the most effective way to keep focussed, stay still, and stay energised, was to keep eating.

Every now and then, in a bout of procrastination, I would spend all day baking – fruit bread in the bread maker, lemon muffins, cookies, chocolate brownie. I proudly presented these gifts to my flatmates, thinking I was being so kind and nice and helpful.

The baking sat there, uneaten.

I couldn’t let it go to waste.

So I ate nearly all of it over the next few days.

“We used to always have money in the shared flat account. Where’s all the money gone? How come it’s barely scraping enough together for dinners now?” One flatmate asked the room as dinner was being made one day.

“We used to use our own money to get food we wanted that no one else was going to eat.” One flatmate said.

“There didn’t used to be baking.” Another chimed in, with a hint of derision.

“Also we didn’t have any students living here.” The word was spat out like a curse word.

A couple of the flatmates moved out.

New flatmates moved in and the collective kete shrank because they wanted to do their own food. I tried to gently ask them why they didn’t want to share food with us. “There’s too much baking, and that’s not what we want to spend our money on.”

Wait. What? Was there not normally copious amount of baking in every house?

They made it sound like I was the problem. Like I was doing something wrong. Here was me thinking I was doing them all these favours by buying groceries so they didn’t have to worry about it, and baking for them, and they made it sound like that was problematic. The ungrateful schmucks!

Baking is delicious.

Who wouldn’t want baking???

Turns out the answer was everyone else except for me.

Baking was expensive. And unnecessary. And perhaps not super good for you.

I got the gist, but I was too far in now. I actually couldn’t stop. I should’ve just said ‘yea, it’s fine, I’ll buy the baking stuff myself out of my own money.’ But I, being a student, didn’t really have any. After rent, there was about $50/week to my name.

The more baking I made and ate, the more baking I needed to keep going. It wasn’t limited to sweets, I made pizzas, corn fritters, bread and loads of things. I just loved creating. It was a welcome reprieve from the stress and boredom of study.

Also, I didn’t know how else to do food. Full fridge, full pantry had been my normal all the days of my life. I didn’t know how to change speed, particularly not when I was so stressed out about teacher’s college.

Unlearning took time, energy, and effort I didn’t have.

In the beginning, I had just been innocently doing a bit of baking here and there, but by the end, I NEEDED the baking, I needed it to keep going. And if I didn’t really, then I certainly, if nothing else, believed I needed it. And that was enough to make it true. I didn’t have the headspace to contemplate another way of doing life.

I got a job in Auckland, and moved out early January.

I suspect the flat food account went back to having loads of money in it after that.

It is one of those years that I look back on and cringe, but I didn’t know how else to get through.

And, alas, it was only just the beginning of my propensity for bribing myself to get work done that I didn’t want to do.

Was I addicted to food? Yes, I needed food to live. Was I addicted to unhealthy, salty, sugary food? Seems like maybe I was. I just thought that was normal. That I had it under control. That I could run it off.

First year teaching was much the same. Keeping going for 12-16 hour days by eating to compensate for fatigue, stress, combat impostor syndrome, and to hush feelings of inadequacy.

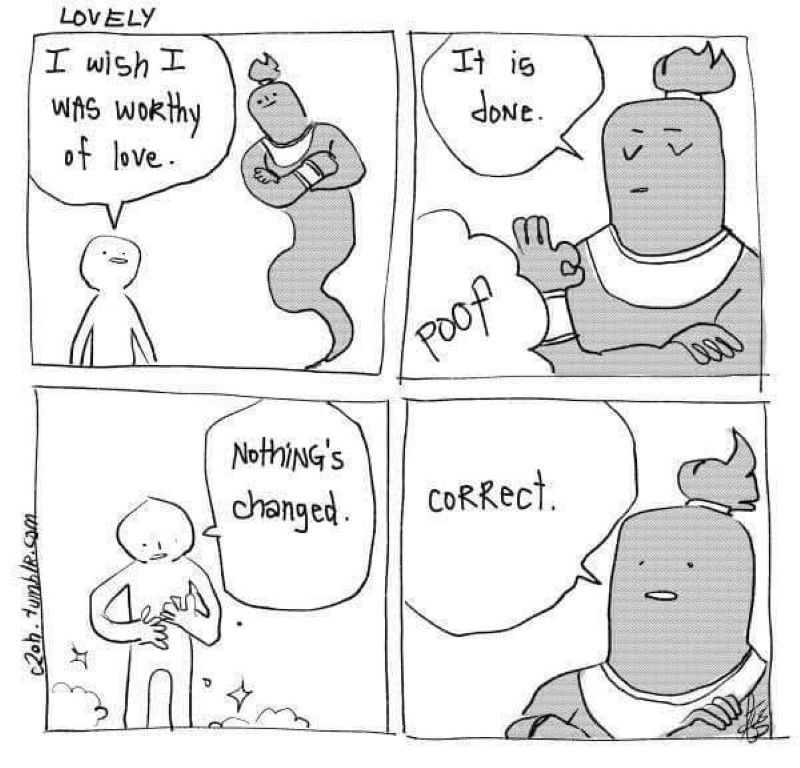

In my mind, there was this gap between what was expected of me to be a competent, capable individual, and what I was actually willing and able to do, and I bridged that gap with food.

Good food. Junk food. Coffee. Alcohol. Everything was a salve to the idea that alone I wasn’t quite enough. That alone, just me, with no additives, I would not be ok. I would not be able to do this.

I was not enough.

It worked, to a certain extent. It kept me going when everything else seemed utterly insurmountable. Cookie Times and Whittaker’s chocolate became my shield. It was no longer want, but need. I couldn’t possibly do all of this without [____] – coffee, lollie cake, McDs, Thursday night dumplings at the Chinese restaurant around the corner with my other stress-eating teacher friend, cheesecake from the Cheesecake Factory – and on and on the list went.

Brains default to deficit thinking, scarcity thinking. Our default is that we are fundamentally not enough, and need something else, something external to give us the X factor.

I wondered if I’d made the right decision, if teaching was for me, a lot that year. I heard my father’s cautionary words ringing in my ears:

“So you’re going to teacher’s college?” My Dad asked. I could hear the wince in his voice.

“Yep, it ticks all the boxes – pays me to talk, keeps my brain active, contributes to something larger than myself, it’s fun, and allows me to travel.”

“I don’t think you really know what you’re signing up for, Lauren.” (Who of us ever really knows what we’re signing up for?)

“What do you mean?”

“Well, look at your Aunty. She has no life outside of teaching; it is her everything. That’s the level of commitment you have to give if you want to do it well, and I know you will. I think eventually you’ll hate it, because it’ll stop you from hanging out with your friends. It takes over your life, and you lose balance. You won’t have as much time for exercising. Are you sure that’s what you want to do with your life?” Well I was pretty certain before, but now I was adamant – I had to prove him wrong.

What he didn’t say, but I heard, was if you go into teaching, you’re going to get fat, really fat, and I don’t want that for you.

Surely, there must be a way to be a teacher and still stay fit and healthy, and have a functional social life? My extended family is not known for their ‘balance’. I come from a long line of workaholics.

But I was going to break the cycle. I was determined I was going to find a way to have a social life, be an awesome teacher, and generally win at everything forever.

I had made my begrudging peace with being a bit bigger – all the teachers in my family were. It seemed like a fait accompli. I was sassy, sizable, but still worried that people would love me less for being bigger.

It seemed my options were to be poor and skinny working in a cafe or something, or larger and richer working as a teacher. There wasn’t enough time in the day to ‘work off’ all the calories I’d put in to keep going. The calories needed to go in, otherwise I was convinced I couldn’t do my job.

When I am stressed out, comfort eating is a really effective strategy to feel better. But it’s a pretty hedonistic, short term solution, and doesn’t address the underlying problem: the stress.

Overeating as a coping strategy for stress isn’t new. Similar to the idea of ‘kummerspeck’ in Part 6, there’s something about overeating that convinces our brain that everything will be OK.

Whether it was moving to another country, doing a really tough course at uni, or my first year of teaching, there was something to this strategy.

The science behind it goes like this:

“In the short term, stress can shut down appetite. The nervous system sends messages to the adrenal glands atop the kidneys to pump out the hormone epinephrine (also known as adrenaline). Epinephrine helps trigger the body’s fight-or-flight response, a revved-up physiological state that temporarily puts eating on hold.

But if stress persists, it’s a different story. The adrenal glands release another hormone called cortisol, and cortisol increases appetite and may also ramp up motivation in general, including the motivation to eat. Once a stressful episode is over, cortisol levels should fall, but if the stress doesn’t go away — or if a person’s stress response gets stuck in the “on” position — cortisol may stay elevated.” Ref

Furthermore, the bigger the stress, the poorer our food choices become. We dive for the salty, fatty, sugary goodness. Our brain is convinced this is necessary to keep us alive, to overcome this ongoing stressful challenge.

When you compound this by getting poor sleep, not exercising enough, and drinking to take the edge off – the classic Western quadrangle of the ‘stressed out lifestyle’ – it is a four pronged approach to weight gain, an endless feedback loop of fatigue, coping, and hunger.

Is it any surprise that if I believe the thought ‘I am not enough by myself’ that my brain and body are constantly yearning for ‘more’?

While overeating may instantaneously cure the feeling of stress, it does lead to longer term consequences, which we will explore more in coming weeks.

How do you go with differentiating between tiredness and hunger? What non-eating stress relieving solutions do you use? If stress is a factor for you, what can you do to cut some stress out of your life?