Myth #6 You have to eat all the food on your plate

Myth #7 Potlucks or buffets are a good idea for those who are inclined to binging people

In 2006, aged 19, I went on holiday to Australia with my then-boyfriend and his family. His mum prepared dinner one night, and brought it out so we could dine al-fresco style on the patio. It was a small plate of maybe a dozen chicken skewers. To feed 7 of us.

The plate was demolished in about 5 minutes, with everyone taking one, then the more assertive among us taking a second.

“Well, that was a nice snack, where’s the rest of it?” I jokingly said. No dinner that I’d ever participated in was that small.

I soon found out that that was it.

I don’t remember being hungry afterwards. I just remember marvelling that that was ‘enough’.

A friend, years later, told me about a study that said if you gave people a full dinner plate of food, and asked them to eat blindfolded until they felt satisfied, most would only eat about half of what was on their plate. Turns out it was 20% less, but the principle stands.

How do you know when enough is enough?

My childhood was filled with a host of potluck lunches at church and Pathfinder meetings – all you can eat.

Every fortnight, the pizzas would arrive from pizza hut and signal that basketball time was paused. There was a definite pecking order of food on the potluck table: professional pizza first, then when all of that is gone, home made pizzas, then after that any savouries, then chips, then whatever else happened to be on the table. There was limited professional pizza; you had to be quick.

At home, my Mother – domestic goddess – would always err on the side of feeding us too much, rather than too little.

Part of Mum’s success criteria as a mother was feeding us utterly amazing food. If food was a love language, then that was hers. There always had to be baking in the house – for school lunches, of course – it’s better for you than that crap from the supermarket.

Brooking family gatherings? Well, you were definitely not going to go hungry there either.

My Dad was the worst for it – give me stick for being a bit pudgy, and would then also have eating competitions with me, and man, he could put it away.

I wasn’t about to be backing down from a challenge – I inherited the competitive gene from him. Valentines restaurant before Christmas became a challenge to ‘get your money’s worth’, and Christmas dinner we were encouraged to eat up, because there was so much food. (Om-nom-bligation)

Mum would occasionally trot out things like ‘You’re supposed to leave the table feeling like you could still eat more’ or ‘Chew slowly, then you feel more full’ or ‘It takes 20 minutes for your food to get from your mouth to your stomach,’ but I was busy racing my brothers to see who could finish their food first. Usually it was Peter, but I gave him a good run for his money.

If ever we got to the stage where we were ‘full’, and we still had things left on our plate, we were encouraged to finish it anyway, praised when we did. Mother knows best. She didn’t want kids complaining they were hungry later on.

Good eaters, we were called. Healthy appetite. Eat all your food, so you can grow up big and strong. I never left my crusts behind. I was set.

This taught me that I was full when my plate was empty, and if I eat my food fast enough, I can fit seconds in. Why would you not want to? It was delicious! Probably – definitely – not what I was supposed to learn, but in teaching, that’s called the ‘unintended curriculum’.

As teens, when we went for movie days with family friends, we would see how many slices of pizza we could eat – Peter definitely winning that one, downing an entire pizza by himself. It was a mark of superiority to be able to eat that much. Through the teens, as our bodies were growing, it was a way of exploring our new bodies, pushing them to the limits, seeing what the new non-child parameters were.

Mum would get annoyed that we would eat everything before she could have it for a ‘Leftovers Dinner’, often scoffing it straight after school instead of waiting for dinner time.

We were growing. It was fine, right?

There was never a conversation about ‘That might maybe perhaps be too much food’. Not one that I remember listening to anyway. Besides, she’d only just gotten me eating again, she wasn’t about to start limiting me.

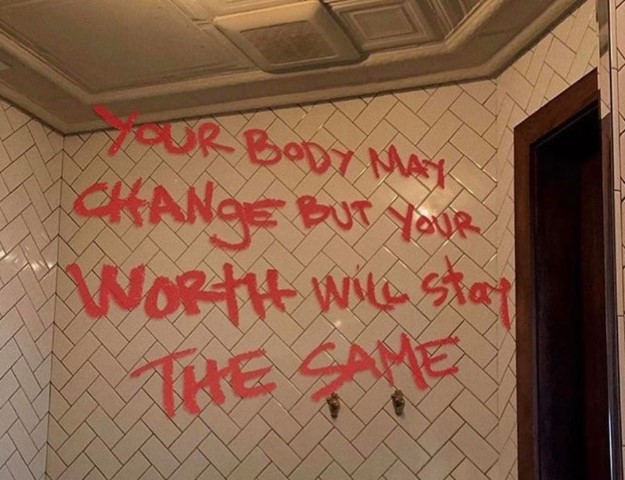

Over and over and over again, the message that the external obligation to ‘finish this little bit up’ or ‘don’t leave that stupid little bit’, or ‘don’t let it go to waste’ was praised, reinforced, rewarded over ‘listen to your body’ or ‘find what is ‘enough’ for you’.

Overindulgence became glorified, a hobby, a competition, a right. Expected. The norm.

My threshold for ‘enough’ kept growing. All nighters for assignments at uni was hungry work, and well, someone had to eat the fundraising muffins that didn’t get sold. Take one for the team. I couldn’t very well throw them out, could I?

Later in 2006, I had a job selling fruit over summer. I discovered that walking for kilometers and kilometers every day whilst carrying about 15kg of fruit at any given time was quite satisfying work. To date, it is probably the job that has utilised all the very best of my skills at once. But amongst this I discovered a great life hack: If I was doing physical labour all day, I didn’t get hungry.

In the month I was doing that job, I dropped down to about 1.5 meals a day. Massive breakfast, then kind of ‘eh’ about the rest of it. This was heretofore unheard of – I always finished my food – that’s how I’d been programmed. I lost something like 10kg in a month, my skin cleared up, I had loads of energy. I was living my best life!

Turns out I was built for manual labour and sales. Not hungry was a great bonus, but what job could you get that was physically active all day and actually paid decent money? None that I could think of. Certainly not one that justified the time and expense of the degree that I was just finishing.

Around Christmas, we went to another buffet dinner, as was tradition. “You’re looking well, Lauren. Fruit selling must agree with you.” My Dad commented as we sat down.

“It does seem to.” I grabbed a side plate of my favourite food, and ate just that. Dad took one look at my plate, and commented, “Well, we’re hardly getting value for money if that’s all you’re eating.”

There was no winning. I was damned if I did eat, damned if I didn’t eat.

The same trip to Australia in 2006 also included lunch at my boyfriend’s Auntie and Uncle’s place. It was a scrumptious affair, with carefully portioned plates of food, and a cheesecake for dessert. His Auntie carefully sliced two cheesecakes into 6 slices each. Some at the table declined dessert. There was some leftover.

‘Would anyone like another piece of cheesecake?’

‘No, I’m so full! Thank you so much for lunch.’ I said.

She went and tipped the rest of the cheesecake into the bin. ‘We don’t normally have cheesecake in the house, you see,’ She said in explanation when she came back in the room and saw my face, aghast.

‘If I had known you were going to just throw it out, I would’ve made room for it!’ Cheesecake was a favourite of mine.

‘But you said you were already full. There comes a point, where your body has had sufficient nutrients, and putting more food inside your body then becomes exactly the same as putting food in the bin.’

It was one of those moments where the world seemed to stop spinning. Throwing out food is the same as putting it in my body? It’s OK to throw out food?

These were entirely new concepts.

I had had enough.

My body was not a human garbage disposal unit.

It didn’t serve me to use it as such.

How much was enough?

Our concept around ‘enough’ is greatly muddled by scarcity mindset – where we think we’re going to run out of something, we act very differently around it. When we think there’s loads of a thing – abundance – then usually we’re nonplussed, and do not want – need – very much of it at all. Finding the right amount, your ‘enough’, is easy when there’s loads.

How can you tell when you’ve had ‘enough’?

When you’ve been raised in a home of ‘healthy eaters’ there’s a very real fear that the thing you really want to save for later might not indeed be there later. Scarcity. And so sometimes, you eat just so that no one else will.

2020 saw scarcity mindset in action in our grocery stores – as soon as people thought they might miss out, they too started hoarding things that they didn’t really need. This dietician says that the antidote to this is ‘abundance mindset,’ a little bit of the old reverse psychology. As soon as we can have it as much as we like, we find we don’t need or want it as much anymore. If you can have donuts and ice cream for breakfast as much as you like, and you give yourself permission to do that, the appeal will very quickly fade after you gorge yourself and feel ill a couple of times. (Or maybe you’ll feel great, who can say?)

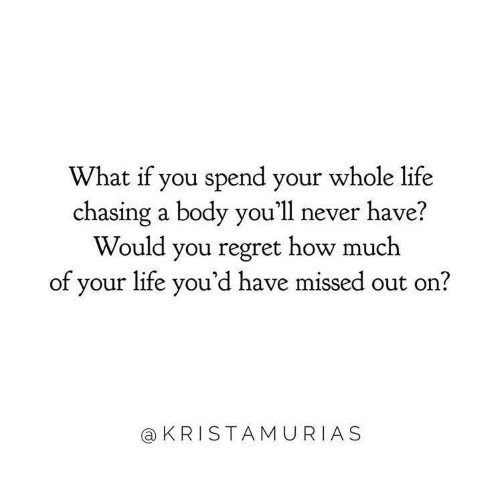

But long before I’d figured any of that out, I broke my ‘enough’ gauge. That’s what binging does. What do you do when your ‘enough’ is exceeded? Do you keep going anyway? Do you have to finish everything on your plate?

If you override ‘enough’, and do that often enough, does it move the threshold for ‘enough’?

Yes, yes it does.

In 2008, I moved to Laos. My lifestyle transformed overnight and became the typical office worker’s. Sitting at a desk all day, my soul slowly rotting inside of me from lack of people interaction, and the physical effort required to be still and quiet all day.

That was the year that the equilibrium broke, and I discovered the truth that my ‘enough’ is very small, and I couldn’t outrun my fork. Next week, we will discuss the impact of exercise on weight loss.