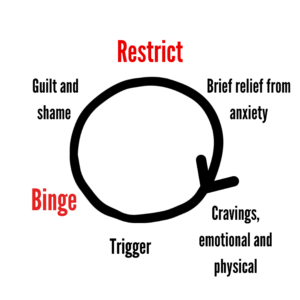

Myth #2 Starving yourself will make you skinny

Myth #3 Eating food is better than it going to waste

Myth #4 Telling people who have issues with disordered eating to ‘just eat’ fixes the problem

Myth #5 Eating disorders are about food

At Intermediate, we were leaving Mrs Twomey’s class after a French lesson one day and my friend Helena just didn’t get up. I went to help her, thinking she was just messing about, and she slothed into my arms, ragdoll-like.

She’d fainted.

She was the one who I’d copied not eating lunch from. Was fainting part of the process? She came to a moment later, and went to the sick bay. She was back in class about an hour later, like nothing had happened

At high school, I would take exactly 6 crackers, and 2 slices of cheese for lunch. Eating it was optional. I have always had a weakness for all things sweet, so occasionally would swap out cheese and crackers for a Cookie Time Cookie – triple chocolate, of course.

This was also the time that my Mum had a catering company, so there was an endless supply of cakes, leftover club sandwiches, slices, biscuits and food of amazing tastes and flavours. There was usually a carrot cake or lemon yoghurt cake that needed eating, and well, saying no to sandwiches was one thing… but cake? There should always be a ‘yes’ to cake, especially with cream cheese icing – the shelf life is rather limited after all.

‘Eat it up, I don’t want to have to throw it out!’ My Mum would say. Whether we wanted it – or needed it – was not brought into the equation. Ever the people pleaser, I was happy to oblige, it was delicious, and because – CAKE!

And so the pattern of obligation to food commenced – putting the need to ‘use up’ food before listening to my body about whether or not I was hungry. (Om-nom-bligation.)

‘Just finish that silly little bit up, Lauren’

I would starve at school, then come home and binge, having ‘earned’ the food from PE, and walking to and from school.

After a near-fainting incident at school one day, I got hauled into the guidance counsellor’s office.

“Right, Lauren, what is going on?”

“I didn’t quite get around to eating today. Then I felt a bit faint.”

“Is this the first time this has happened?”

I smirked. “Nope.”

Mrs A tried to cover her shock. She got out her jotter pad, and drew a (quite rotund) picture of a person, and illustrated a cycle. ‘When you starve yourself, your body freaks out and holds onto the fat so you don’t die, and then when you do eat, your body stores it as fat, because it’s not sure when you’re going to eat again.’

It was not the first time I’d gotten near fainting. I had gotten pretty good at starving myself, and honestly, it came mostly without incident, because it was the starve-then-binge pattern. However, sometimes when we were doing PE at school, or when I was in a really hot shower or bath, I would get quite light-headed.

When I went on camps in the holidays, I would not eat for days at a time as my whole system was protesting about being away from home, and digestion would cease. So I would just eat the dessert – because if you’re eating, it should obviously be the good stuff – and skip everything else, unphased, genuinely not hungry, because I actually need very little food in order to function, instead energised by fun and being surrounded by people.

I thought that feeling faint every now and then was just part of the package of being skinny, and thus being beautiful and cool. Not a bother. If that was the price of admission into the skinny club, I would pay it. I didn’t know how else to get skinny other than starving myself and copious amounts of exercise.

But with this new information, I decided that perhaps that was enough starving myself, and decided to resume eating. If depriving myself of all of this food was not actually going to achieve the goal, then CAKE!! I shall be having all of it. In classic black-and-white thinking common to high-achiever, control-seeking, perfectionist types, I went from nothing to all in the matter of a few short years.

My people pleasing was now torn between adults that wanted me to eat, and me and [society] wanting me to be skinny. I didn’t know how to do both.

I had no real guidance of what a healthy eating plan looked like other than ‘eat fruit and vegetables’, so going from eating a little to eating a normal amount had little or no parameters.

People just wanted me to eat.

My new logic went something along the lines of

‘I’m an Adventist.

Adventists have healthy eating as a doctrine.

My mum cooks us ‘healthy’ food ∴ whatever she makes must be amazing, healthy, and legitimate ∴ I can have loads.

Nothing could possibly go wrong.

I run lots ∴ It’ll be fiiiiine.’

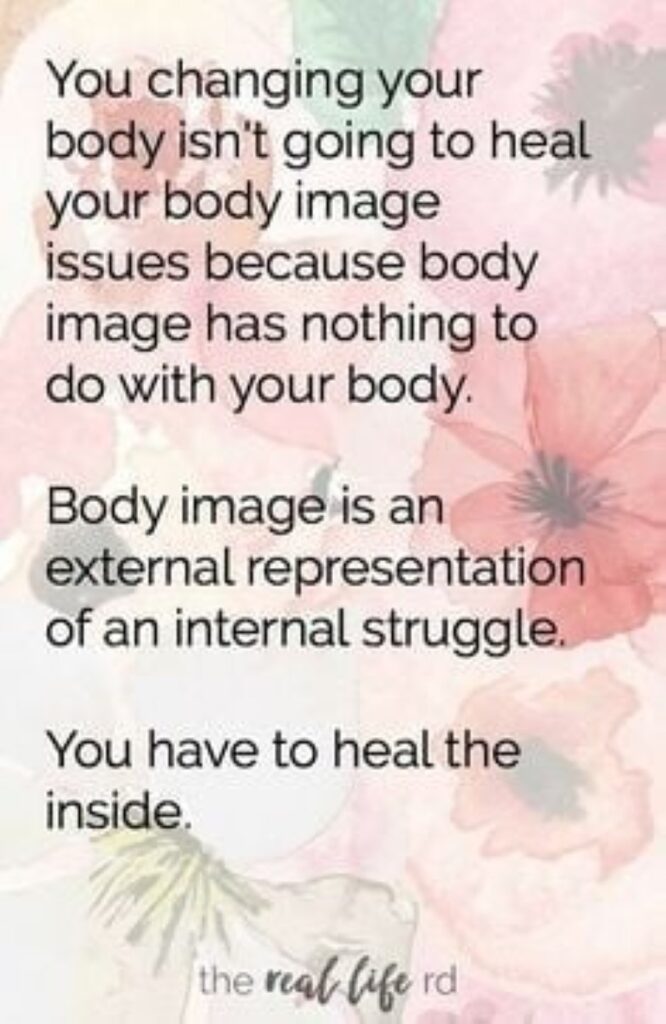

Eating didn’t change the problem that my self-esteem was coupled to my size.

It didn’t satiate my ardent desire for affirmation or attention, or the fact that I believed that affirmation was conditional.

It also didn’t change the fact that I’d trained myself to binge eat.

And then exercise to compensate.

We would often have chocolate self-saucing pudding after dinner, and it was amazing! We were allowed three different flavours of ice cream – there was usually a staple of 3-5 different flavours in the house – Chocolate chip eclair amongst them.

I would then run laps of the concrete area of the backyard – I measured the length of it and I would carefully count my laps. I would run kilometers when my mother had dubbed that it was too dark and scary for me to be going out for a run alone on the streets, aged 13.

———

Fast forward to my early twenties, when I was swimming 1km weekdays, walking 8km a day, and had given up sugar. I was the slimmest I’ve ever been before or since. I *almost* felt worthy of attention. I had a FWB arrangement with a guy I met working at Parliament, a sardonic, witty, cerebral guy, who every now and then I would meet up with, and afterwards would always vow it was the last time.

‘You look amazing. I’m just a grumpy, prematurely-old, pudgy bastard.’ He bemoaned post-coitus one evening. I have always had a soft spot for the self-deprecating ones.

‘Yea, but I work really hard at that.’ I worked really hard at that, because I understood men’s favour to be conditional on being sexy. I’d equated being sexy with being thin. I’d already swam my kilometer for the day, and walked to and from work, before walking around Island Bay with him for a good hour. I convinced myself to get into the pool even when I didn’t want to with mantras like ‘this will help you look good naked’ and ‘being thin gives guys one less reason to reject you.’ I just wanted to be liked. Admired. Loved. Was that so much to ask? ‘Besides, I like you just the way you are.’ That was what everyone wanted to hear, right? It also happened to be true, much as I might wish to turn it off.

‘But it’d be better if the flab was gone and I was really buff, right?’

‘Eh, would it? I feel like it wouldn’t much matter. I like you for your terrible jokes and lame factoids. And buff guys… well, they’re not generally very nice, or interesting.’

So this is what all those guys felt like when they had tried to convince me I was beautiful, regardless of my size. Huh.

We met up about a year later – actually for the last time – and he’d lost loads of weight.

‘Wow, you’re looking really good!’

‘Wish it was from training.’ We used to do martial arts together.

‘Oh? Is it not?’ I asked.

‘Na, I’ve been really sick. I basically can’t eat anything. Which means now I basically can’t drink either.’ He had been drinking every night since his step-father had passed away, around the time I met him three years prior. ‘Besides, anyone who’s tried to drown their sorrows in the bottom of a bottle eventually realises that sorrows float.’

Skinny didn’t always mean healthy. Boys also have body issues. This guy was now sober.

Tonight was weird.

He now fitted the skinny ideal, his BMI would be in the healthy range, but he was sick. I looked amazing, but I was a slave to others’ admiration and approval.

Skinny does not always equal healthy. Not physically, nor mentally.

Skinny certainly doesn’t seem to equal happy.

Nor does skinny equal self-esteem.

There has to be a better way to think about all of this.

Next week, stick around as we explore further our rocky relationship with food, and what healthy really means.